The publication edited by Rimisp continued its route through Latin America with meetings in the Sierra Norte de Puebla and...

Opportunity and mobility: what Latin American families teach us about inequality

Text written by the researchers Chiara Cazzuffi, Thibaut Plassot and Isidro Soloaga authors of papers developed within the framework of Rimisp’s project “Transforming Territories”..

In Latin America, most parents want their children to go on to higher education. However, many do not believe that this will actually happen. This gap between aspirations and expectations, that is, between what is ideally expected and what is perceived as possible, reveals a deep dimension of inequality. This inequality is not only determined by family origin, but also by the territory in which one lives.

Recent research, comparing data from Chile, Colombia and Mexico, shows that this so-called “feasibility gap” is common in intermediate territories. These territories are located between large cities and more isolated rural areas. A significant part of the population lives in these areas in each country. In Colombia, 60% of parents who want their children to complete higher education do not believe that they will do so. In Mexico, the figure reaches 40%. In Chile, on the other hand, the gap is reduced to 10%. This coincides with increased participation in tertiary education in Chile.

This difference between desire and expectation is not just a psychological phenomenon. It reflects a structural reality related to territorial inequality.

In our study we use data from the Survey of Territorial Dynamics and Well-Being. This survey is representative of the intermediate territories in each country and allowed us to compare what adults want for their children’s education with what they believe is actually possible to achieve. Based on this information, we analyzed the magnitude of the gap between the two aspects.

The results are clear. In all three countries, socioeconomic status, as measured by the education of the primary caregiver and a household asset index, influences aspirations and expectations. However, the alignment between the two does not depend solely on household resources. Where the family lives also matters.

Residing in the urban core of the intermediate territory is associated with higher expectations and a lower feasibility gap, even when controlling for other variables. In addition, local educational quality, as measured by standardized test scores, is also associated with higher expectations and a more optimistic perception of the educational future.

This indicates that the geography of opportunity does matter. When local opportunities are scarce, even those with high aspirations may not believe they will be realized.

In a second study we address this issue from another perspective. We analyze intergenerational social mobility and inequality of opportunity using a joint analytical framework. In this second research we also compare Chile, Colombia and Mexico.

The results show that relative mobility is higher in Chile and lower in Colombia. In turn, inequality of opportunities is strongly influenced by territorial characteristics, especially in Chile and Colombia . In these two countries, the place of residence explains a considerable part of the differences in the economic outcomes of adults, even more so than in Mexico.

Both studies point to a common conclusion. Territory is not only the scenario where inequality occurs. It is a factor that reproduces or reduces it. From childhood aspirations to adult achievements, place of residence can facilitate or limit life paths, beyond individual effort or talent.

The findings provide solid arguments for rethinking equity policies. Strategies focused on households, such as cash transfers or training programs, need to be complemented with policies focused on territories.

If the quality and availability of education is not improved at local level, and if the structural disadvantages of intermediate and peripheral territories are not addressed, the risk is to maintain a pattern in which hope exists, but is not accompanied by a real belief in its fulfillment. And when there is no realistic expectation, aspirations are not transformed into achievements.

When mothers and fathers aspire but do not expect, we are not facing individual frustration, but a collective signal. This signal speaks to us of how inequality is experienced in the different territories of Latin America.

Closing the feasibility gap and expanding social mobility requires attention to this signal. And it requires responding with policies that accompany people, but also the places where they build their life projects.

News

Country News

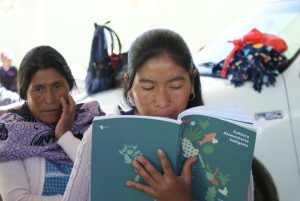

Pre-launch of the book “Indigenous Food Culture” is held at the Misak barter fair

In the Resguardo de Guambía, municipality of Silvia, department of Cauca, Colombia, the first pre-launch of Rimisp's publication took place....

Rimisp webinar addresses the future of indigenous food systems

The closing event of the "Networks for Agrifood Transformation" project offered a space for dialogue on the projections and challenges...

Subscribe

Our offices:

- Chile: Huelén 10, Providencia, Santiago, Metropolitan Region (+56-2) 2236 4557 | Fax (+56-2) 2236 4558.

- Ecuador: Czechoslovakia E9-95 between Switzerland and Moscow. Eveliza Plaza Building. Ground Floor. Quito. (+593-2) 5150144.

- Colombia: Carrera 9 No 72-61 Office 303. Bogotá. (+57-1) 2073 850.